The female olympics was part of a long line of Olympic history. The Olympic Movement of the late-19th century, which led to the revival the ancient Greek tradition of the Olympic Games, was successful thanks to the efforts of two distinguished gentlemen ― Pierre de Coubertin and Demetrius Vikelas.

The first modern Summer Olympics was held in Athens in 1896, starting what is today known as arguably the most important sports event in the world.

The Olympic Commission made it their mission to revive the traditional games and therefore celebrate the spirit of ancient Greece in every way possible. Among other things, this meant strongly discouraging women from taking part in the competition, as in ancient times women weren’t even allowed to be in the audience, let alone participate.

heir arguments reflected generally the accepted opinion of the era ― that in order for women to preserve their feminine charms, they must be excluded from such manly activities.

They also relied on the conviction that women were just incapable of performing well and that all of their attempts to do sports were too amateurish.

However, the century that followed brought great changes in terms of women’s rights, and the status of women in society in general.

In the wake of the Suffrage movement in Europe and the United States, as well as the Russian Revolution of 1917, women were quickly becoming political subjects who demanded their voice to be heard.

In such a political climate, female athletes felt encouraged to act — to fight the prejudice that sports were an activity reserved for men only.

It took 16 years from the time the first modern Olympics were held in Athens for women to gain very limited access to the competition.

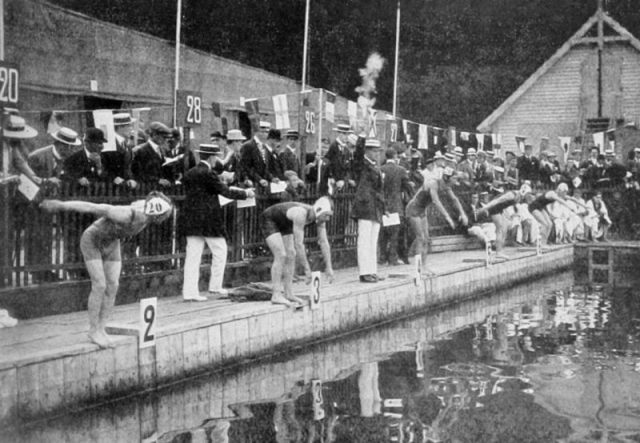

In Stockholm, in 1912, women were permitted to compete in swimming and diving, with 22 female athletes taking part. However, this giant first step was not welcomed by all.

Pierre de Coubertin famously commented that:…“an Olympiad with females would be impractical, uninteresting, unaesthetic and improper.”

Seeing that they were not taken seriously by their male counterparts, a group of women, led by Alice Milliat ― a pioneer of woman’s sports in Europe ― organized the first ever international women’s sporting event, which took place in Monte Carlo in 1921.

This was done partly as a reaction to the stubbornness of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) ― at the time still headed by its founder, Pierre de Coubertin ― to make the games more available to women. The 1921 Women’s Olympiad served as a forerunner of the Women’s World Games, held for the first time during the following year.