EVERY TIME I THINK OF the remote wilderness, I think of people. This is not the contradiction it seems. As a child, I grew up marching around some of the most isolated terrain of Alaska. But almost always, I was out there fishing for king salmon, hunting for caribou, or hiking up a shale-covered mountain with my father or mother or grandmother or a family friend as close as any family. (There is nothing that will bind you to another human being like sitting in a raft together as it overturns in class IV rapids a few hundred miles from civilization. Especially if that other human being somehow possesses an extra pair of dry socks.)

What worried all the grown-ups in my young life were “the other people.” We had to get away from them. Though I didn’t fully understand, I did agree that these mysterious “other people” might catch all the salmon or scare off the bighorn sheep. But that seemed silly. The rivers were loaded with fish, the alders all too thick with wildlife. When I did see another boat filled with humans on a river, I would look at them in wonder — their appearance rarer than that of a bear or a moose. Why couldn’t we just invite them to camp beside us and make friends, I thought, instead of nodding silently, then waiting for them to float off?

Only as an adult, now living far, far from the subarctic bush, have I begun to appreciate the heroism of my parents’ intentions. Wandering alone in the wilderness is a distinct experience, a luxury in an age of less and less aloneness (thank you, Facebook) and less and less wilderness. There is a glamour to slipping off the coil of civilization and walking into the trees with a tent, tin cup, and bag of matches. Fantasizing about such an experience is, in many ways, a national pastime — one that motivated our forefathers to move west to the frontier and, from there, north to the Last Frontier.

Today, so many of us routinely click off the sales report at work and click on cabinporn.com or stare endlessly into the terra-cotta firepit in our backyard wondering, What if I just took off — into the woods? Out there, we tell ourselves, it’ll be simpler. I’ll be free from the noise, the cubicle. Everything will be different. I’ll be different. But how would we be different?

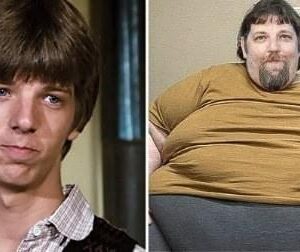

IN 1968, two years before I arrived in Alaska as a newborn, a 51-year-old heavy-machine operator named Dick Proenneke decided to build a cabin on the remote shores of Twin Lakes and live out his version of the alone-in-the-wilderness dream. Let me clarify what I mean by remote: Twin Lakes is a 20-minute flight over (or 48-hour hike through) bear-infested, buggy wilderness from a tiny village called Port Alsworth, which in turn is an hourlong flight from Anchorage (if the pass through the mountains is not fogged in), which in turn is a five-hour flight from Seattle.

Dick was what he himself called “an oddball.” He refused to build the cabin with anything other than hand tools, to avoid the noise and smell of chain saws. Having worked in the Navy as a carpenter and then in Alaska as a diesel mechanic, salmon fisherman, and U.S. Fish & Wildlife employee, he had developed skills that not only made his self-imposed rules feasible but also appealing. To Dick, moving to an isolated lake to live off the land was retirement. In his journals, Dick describes dragging logs for up to a quarter-mile with a homemade forehead harness, constructing a sled for travel across the ice, planting potatoes in the permafrost, and cooking sourdough biscuits over his barrel stove.

His one-year experiment turned into three decades, give or take the odd winter. In 1973, he turned his journals into a book called One Man’s Wilderness. In 2004, a producer in Colorado named Bob Swerer used parts of the book to narrate a film, which debuted on PBS. The film is a grainy, 16-millimeter marvel, shot by Dick himself during his years on Twin Lakes. The plot is simple: Man builds cabin in wilds of Alaska, proceeding step by step from the notching of each log to the application of a sod roof, with assorted pauses to cook hotcakes, view wildlife, or make meditative observations like “What a man never has, he never misses” and “It is surprising how comfortable a hard bunk can be after you come down off a mountain.”

The title of the film: Alone in the Wilderness. By now, it has been seen by countless millions of viewers. Most of its devotees, I am willing to bet, watch it with the same mixture of worship and fantasy as I do. Dick being Alone in the Wilderness makes Me Being Alone in the Wilderness seem viable — one day. Dick notches logs as if they were butter and catches fat lake trout on a first cast. Dick does not swamp his canoe, fall through the snow on his snowshoes, or forget to stuff chicken wire in the open holes of his cabin roof, allowing wild squirrels to eat up all his kitchen supplies. It’s just that easy, he seems to say, splitting planks out of thick tree trunks with one swift, nonchalant heave of the ax. Try it.

Let me explain: Despite my rugged upbringing, I married a city-loving architect who enticed me to Brooklyn, where I’m now a working mom with two kids. Though it is true that I returned to the bush with more familiarity and experience than the average person, it is also true that I was rusty in terms of skills and lacking in terms of gear, the latter of which included a fly rod (circa 1985) and the buck knife I received for my 12th birthday.

As improbable as it may seem, Dick had had some of the same doubts. “What was I capable of that I didn’t know yet?” he wrote in One Man’s Wilderness. “What about my limits? Was I equal to everything this wild land could throw at me?”

The first thing it throws at me is the view. From the air, Twin Lakes is a long blue dazzle of water weaving between glacier-scored peaks. Waterfalls dribble off the rocks here and there in strings of soft white froth. This close to autumn (read: August), the alder and birches along the shoreline have just begun to tinge yellow. Once we’ve landed, Dick’s cabin peeks out from the foliage, instantly identifiable by its sod roof and American flag. The structure is a national landmark and open to the public to enter and touch anything at will, 24 hours a day currently, the chief caveat being no overnight camping. Each summer, a volunteer couple watches over the property and gives tours to anyone who shows up by plane, by canoe, or on foot. K Schubeck and her husband, Monroe Robinson, were friends of Dick’s back in the day. K is a human hummingbird, flitting from Dick anecdote to Dick anecdote, demonstrating how Dick used to rake his beach every morning and sharing how Dick used to take two warm stones to bed with him that he called “my girls.”

TODAY, THE TOUR INCLUDES me and two brothers from Oregon. This is highly irregular, I find out, in that it’s such a small group. Some 800 people have made the trip here this season — each paying about $1,200 for a round-trip flight from Anchorage. I’m a little disoriented. Seeing Dick’s cabin for the first time in a group is both comforting (more Proennekeheads!) and discouraging. How are we supposed to feel alone in the wilderness when we’re in a group of strangers? How are we supposed to feel like we’re in the wilderness at all, when there are rules, the first of which is No Stepping Off the Gravel Path? (With that much traffic, human footfall kills the native moss and lichen.)

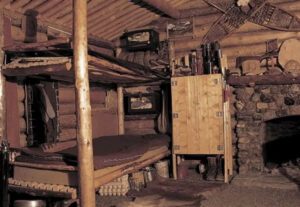

All these thoughts fall to the wayside once we get close to the cabin. It is so tidy, so well built. Cabins in the remote Alaska bush are usually slapdash, mud-chinked affairs, patched together with Visqueen and somebody’s good intentions. This would include my family’s, a plywood structure whose defining architectural feature was a giant black pit where we burned trash.

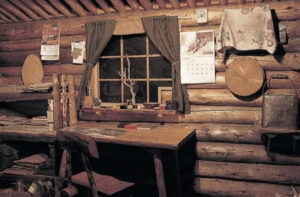

Inside, the cabin looks as if Dick still lived there. A yellowed box of birthday candles is tucked on the kitchen shelf; his calendar sits on his deck, detailed with the events of each day — including the slaying of Porky, a particularly destructive porcupine who wanted to install himself in this cozy abode. (With rare exceptions like Porky, Dick did not hunt after his first year here; he salvaged his meat from wolf-killed carcasses or those left by trophy hunters.) The Oregonians, as am I, are impressed by Dick’s stone fireplace, gravel floor, and inventive Dutch door, whose top and bottom sections open separately. The older brother is a woodworker and experienced outdoorsman. Exiting the cabin, he stops and says in a hushed, almost awed tone, “It’s just so amazing, but … so much smaller than I expected.”

That, K tells me later, is the most common reaction from visitors. Smaller cabins are easier to heat (especially when temperatures reach -70°). But I have to wonder if the amplification in people’s minds is due to how much bigger objects look on a TV screen — or how much bigger things seem when we revere them.

NOT 200 FEET AWAY from Dick’s cabin, the foliage takes over, the relentless Alaska alders alternating with dwarf willows and poplars. Soft green moss blankets nearly everything, broken up by crowberries and freakishly large mushrooms. I am staying a 10-minute walk away, in an old cabin loaned to me by the park service. Even that small distance provides plenty of alone-in-the-wilderness time to reacquaint myself with how long things take in the bush. If you want to dry your socks, for example, you have to gather twigs, split logs into kindling, pile the logs, light the fire, rig up a clothesline, and then watch the steam hiss off your socks for about six hours. You must also complete all these steps without making sloppy mistakes that are so hard to recover from in the bush — such as, say, cutting your hand with your ax or burning a hole in your sock (which can lead to blisters, frostbite, or both).

Little by little, as the chores accumulate — tea, meals, fires, laundry, water retrieval, garbage disposal — time simultaneously shortens and lengthens. Because each activity takes so long, the day is packed. And because I can take as long as I want to complete any activity, the day is open-ended, unhurried. It’s this freedom from time that I realize I’ve missed the most.

Each night, I wait until about 6 and then wander over to Dick’s beach chair, which he placed in front of his cabin, along with a comfy rock for a footstool. The chair was exactly positioned to give him a sweeping panorama of the lake, including the volcanic mountains in the distance, an old hunting cabin in the foreground, and the lake in between, in all its blazing blue. “The view,” he used to tell K, “changes every 15 minutes.” I try to simply sit — and listen. At first I can hear only the lapping of the lake on the gravel beach. Then the snap of the flag on its pole. Then the ruffle of wind in the willows. Just as I begin to realize how much there is to hear, the whole scene changes. The calm lake begins to pick up, sloshing. Great gray clouds move in, yellowing the sky. I check my watch: 15 minutes. Dick, as usual, is correct. But as I sit there, I also notice that it’s me who’s changed. The unobvious has regained its power to capture my attention.

Though the obvious still holds sway. The influx of visitors over the past few years has brought trash — not necessarily big piles of litter, but mostly tiny bits of waste that humans do not smell yet black bears find enthralling: spit-out toothpaste foam (mint!), sandwich wrappers burned in the campfire (melted cheese!).

There are plenty of grizzlies here too. Every morning, as I walk down the gravel beach — alone! very alone! — I find a fresh log of scat, about the width of a soup can only longer, studded with undigested berries. I look at my bear spray. I can see an encounter with a grizzly going down a little like spraying whipped cream into a canyon of teeth.

My love of life on earth, unfortunately, limits the extent of my wanderings. Looking up at the mountains, all of which look tantalizingly hikeable, I feel frustrated — and puzzled. I don’t remember bears being such a problem as a child scrambling around on riverbanks, and I don’t remember Dick worrying about them much either — save for one encounter with a very grumpy sow. Then I realize that being alone in the wilderness is different now, because the wilderness is different. Bears didn’t find us so fascinating in the 1970s. There were far fewer humans around, and caribou, conversely, were plentiful. The massive local herds have dwindled for reasons — climate change? disease? human pressure? — that experts don’t agree on. Time not only lengthens and shortens in the wilderness, it also behaves as it does in our cities, suburbs, and villages: It moves on.

AS THE DAYS PASS, the peaks across the lake show powder. I realize there is more and more to do. And I want to catch a fish. Actually, I really, really, really want to catch a fish. It is a Dick Proenneke–style dream, born of watching him casually toss out a line and immediately haul in a fat, silvery trout.

I try to talk myself down — just in case. It is too early for salmon and the trout in the lake might be fished out. Many streams in Alaska have suffered this fate. Still, the spot where narrow Hope Creek rushes into Twin Lakes looks appealing.

I take my historic spin rod and a red-and-white spoon down to the shore. I cast right where the creek water hits the lake water (fish love a mixing of water) and reel in, dragging the spoon across. There is a tug. Then nothing. It could be a hit — or just a rock on the bottom. I cast again — and bang, my line is sizzling through the water. I reel it in, and up surfaces a 19-inch brown-and-silver lake trout. I bonk it on the head with a rock and cast again. Another fish, just as large but a pink-speckled Dolly Varden. After four fish, I quit, keeping only two, releasing the others. The whole experience takes about 10 minutes — including my victory lap up and down the beach. I am alone. I am not required to be modest or sportsmanlike about my triumph.

That night, I take the fish over to Monroe and K’s cabin, down the shore. Some might argue that I’m breaking the Proenneke aloneness code. But even that code is conflicted. “Man is dependent on man,” he wrote. “We need each other. But nevertheless, in a jam the best friend you have is yourself.” I am not in a jam, I decide. I am in the glorious position of being able to procure my own food and share it, pan-fried in cornmeal and butter, with my fellow human beings.